My parents and I spent Memorial Day weekend exploring Mexico City (#CDMX) for the first time. With only two full days to sightsee, we managed to walk through quite a bit of the Historic District, Colonia Roma (where we stayed), and the charming neighborhood of Coyoacán. Here were our highlights and recommendations:

After walking through the Zócalo--the expansive central square bordered by the National Palace, Metropolitan Cathedral, and Federal Buildings--we decided to tour the ruins of the Aztec Templo Mayor. My father decided to hire a guide registered with the Secretaria de Turismo to take us through the site. Our guide--J. Jaime Baez Jasso (jaixtla_tlalpan@hotmail.com), who we would definitely recommend--walked us through the entire archeological excavation and explained the cosmology and social hierarchy of Aztec society, described the Aztec gods and the rituals that honored them, and pointed out elements from the seven stages of the temple's construction. After two hours, we left with a much deeper understanding of pre-colonial Mexico.

Jaime Baez Jasso

Before leaving on the trip, I made a reservation for us to spend Saturday evening at the Zinco Jazz Club. Over drinks, tapas, and tacos, we heard the spectacularly talented house band play big-band classics by Buddy Rich. The talent was A+, the service and food were solid, but the space is tight and it was very warm despite the air conditioner running constantly. We would highly recommend it as a destination for a winter/spring visit to CDMX.

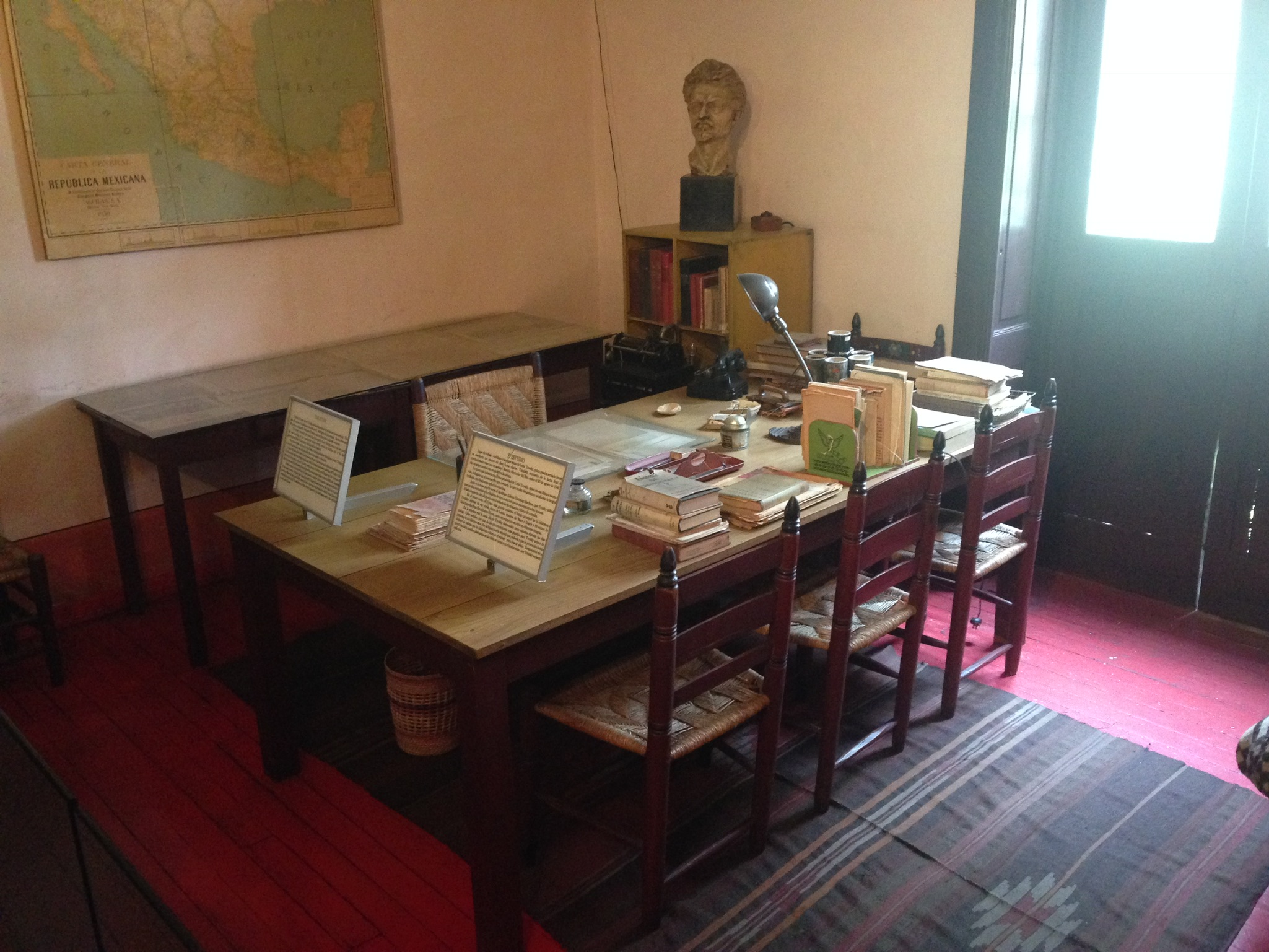

My father, the political scientist, really wanted to see where Trotsky lived out his life in exile in Mexico. My mother and I, while not reluctant, had less investment in the visit--nevertheless, we found it surprisingly enjoyable! As a museum, it's very basic. The house, however, has been preserved and looks as it did in 1940 when Trotsky was assassinated. It's remarkable to walk through and see how sparely he and his wife lived in order to live rich intellectual lives. Trotsky's study and the room where his secretaries worked were filled with books in Russian, Spanish, and English. The walls were also filled with bullet holes from an unsuccessful assassination attempt made in 1939. Although the home is surrounded by a beautiful garden in a charming neighborhood, the presence of the bullet holes, the steel doors and bricked in windows, and the rooms for Trotsky's bodyguards make it easy to imagine how limited Trotsky's life must have been and how little he was able to take advantage of his surroundings.

Leon Trotsky's Study, Museo Casa de Leon Trotsky

One of my favorite things to do when traveling abroad is to go to the movies. It provides insight into how the middle class in that country lives and what their film culture is like, but more practically it's an air-conditioned, comfortable place with clean bathrooms where you can spend two hours recovering from a day of walking and sightseeing. In the chic neighborhood where were staying in CDMX, Colonia Roma, the movie theater was resplendent. Like in Argentina, my only Latin American comparison, you purchase specific seats in the theater. Although they did not recline, the seats were as big as armchairs. Someone came around with an iPad to take our orders for concessions--if only we had known it was an option, we would not have waited in line for a Pepsi. The downside, however, was that the previews included many more commercials than are typically shown before a movie in the United States. In case you were wondering, we saw ¡Huye!

On our last morning, we took a long walk before heading to the airport. From our AirBnb in Colonia Roma, we headed towards Colonia Condesa and the Parque Mexico. Entering the park on a the verdant path, we saw these extraordinary covered wooden benches every few feet. Numerous dog walkers led the most organized and obedient packs of dogs up and down the paths. And then, just ahead of us, we found the densest, most well-equipped outdoor gym that we have ever seen. I have seen exercise equipment in parks around the world, but this one had the widest variety of equipment packed into one area--it truly looked like a floor of a Crunch or Planet Fitness had been dropped into the middle of an urban jungle. We couldn't resist trying out a few. If we'd only known, we would have packed workout clothes and come every morning!